In his famous sonnet, On First Looking into Chapman's Homer, John Keats describes the moment he first came to appreciate some of the great works of classical antiquity. He says he had been told of a domain where Homer reigns supreme—a “wide expanse,” in the “realms of gold,” where “bards in fealty to Apollo hold.” “Yet did I never breathe its pure serene,” he says. Not until he read Chapman’s translations of the Homeric epics. “Then,” says Keats, “I felt like some watcher of the skies, when a new planet swims into his ken.”

In his attempt to evoke the distinct feeling of having found a new world, one that was previously hidden, the poet referenced a discovery from more than thirty years earlier. In 1781, sunlight bounced off Uranus, and into the telescope of William Herschel, who was surveying the sky with his sister, Caroline. At first, Herschel didn’t know what he was looking at. But after inspecting the pale, round dot several times and conferring with others, he determined that it must be a planet orbiting out beyond Saturn, the first such discovery since the Bronze Age, at least.

But not the last. A quarter-century after Herschel died, Neptune was spotted, and decades later, Pluto would follow, before being stripped of its planetary status, unceremoniously, in 2006.

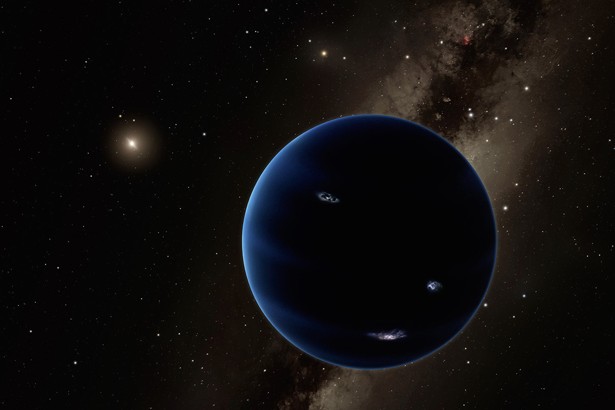

Yesterday, Michael Brown—the very man who demoted Pluto—and Konstantin Batygin announced that a new planet might once again be swimming into our ken. In the debris fields of the outer solar system, at 20 times Neptune’s distance to the Sun, something dark and unseen is stirring chunks of rock and ice into strange orbits. Something massive.

Batygin and Brown say that only a planet could make these disturbances. A planet that was, until yesterday, conspicuously absent. When astronomers zoom in on other stars in our galaxy, they often find planets that are roughly 10 times the size of Earth—and yet, no planets of this size had ever been found locally. Now it appears that one has. Batygin and Brown have given it the unimaginative name, “Planet Nine.” If it’s soon spied by a telescope, as is their hope, it will likely be renamed for one of the gods the Romans stole from Homer’s “realms of gold,” just like the solar system’s other planets. Perhaps it will be Nox, the seldom-seen Roman goddess of night and shadow.

Upon hearing about Planet Nine, I reached out to Freeman Dyson, the 92-year-old physicist from the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton. Dyson is widely regarded as one of the singular geniuses of 20th century physics, which is saying something given how many great physicists that century produced. In the decades following World War II, Dyson did pioneering work in quantum electrodynamics, but he also devoted years of his life to Project Orion, a famous NASA-funded study into whether it might be possible to propel a starship with nuclear explosions. I vaguely remembered him writing something about how objects in the outer solar system might serve as stepping stones in an interstellar voyage, places to resupply and refuel before heading out into the great unknown.

“Would Planet Nine make an ideal waystation?” I asked him. “No,” he replied, quickly. “The galaxy is like the Pacific Ocean, scattered with small islands that are abundant and easy to visit.” But these islands are comets, not planets. “Planets are rare, hard to land on, and harder to take off from,” he said. “Comets are far more abundant and more friendly to visitors.”

What a killjoy, that Freeman Dyson. I wrote him right back: “But would there be any benefit to having another potential gravity assist way out there?” After all, we often send space probes toward Jupiter, in order to use its gravity like a slingshot, to accelerate to the speeds you need to reach Pluto or the interstellar void. I wondered if it might help to have another planet—another potential slingshot—in the outer reaches of the solar system, for when we send a probe or a crewed ship to Alpha Centauri, or one of the other nearby stars.

I waited an hour. Dyson didn’t reply. I felt bad for wasting his time. I tried Steinn Sigurdsson, an expert in orbital mechanics from Penn State University. “Suppose you used a gravity assist from Jupiter and Planet Nine,” I wrote. “Would that help you escape the Sun’s gravity with less fuel?”

“In principle, yes,” he said. “To get a good gravity assist you need to be able to dive deep into the gravity well of the planet to pick up speed, and then fire your rocket at the closest approach. So you want a massive planet, and you want to go as close to the surface as possible.” If Planet Nine is dense, with a shallow atmosphere like Earth, then it might provide a nice boost to a starship. But if it has a thick gas atmosphere and a water-like density, a la Neptune, it “might not be worth going out of your way,” Sigurdsson said.

The caveats didn’t stop there. Sigurdsson went on to explain that Planet Nine’s orbit takes 20,000 Earth-years to complete. “If it’s out there, it is going to sit out in about the same place in the sky for centuries,” he said. That means it will only be useful for certain destinations. Which ones, we won’t know until the planet is confirmed with a telescope. And that’s if it’s confirmed. Across the long history of astronomy, the oldest of the sciences, several predicted planets have failed to materialize. One generation’s hulking sphere awaiting final confirmation is another generation’s textbook footnote.

It was late in the evening when Dyson finally wrote back. “The discovery of a new planet in our system would be a hugely exciting event in many ways,” he said. I thought about it for a moment. Dyson was right. In my rush to ascertain Planet Nine’s practical utility as a starship booster, I’d skipped over the real import of its potential discovery. There might be an unseen world circling the sun, way out in the shadowy depths. A new place to wonder about, and maybe even visit. Who knows what awaits us on its surface?

“Every planet is unique in unpredictable ways,” Dyson said, in his final email. “Unfortunately, the gravity assist that [Planet Nine] would provide is predictable. And it’s small.”

And with that, I closed out my “gravity assist” search tabs, and reached for my Keats.