Oh, hello, my new favorite Internet rabbit hole. The New York Public library has digitized more than 187,000 images, all in the public domain—meaning they’re freely available for anyone to use. And not just that: They’re organized beautifully.

This is a big deal at a time when libraries and other institutions are still trying to figure out how to make their collections digitally accessible. Plopping a bunch of photos, documents, and illustrations online is great, theoretically, but making it easy for people to navigate such resources is much, much greater.

It’s hard to do this. The Library of Congress has for years been hashing out the blueprint for a plan to completely reinvent its card-catalogue system, upgrading it for the semantic web. The latest digitization by the New York Public Library, and a stunning visualization of that work, represents the culmination of a longstanding effort to do something similar.

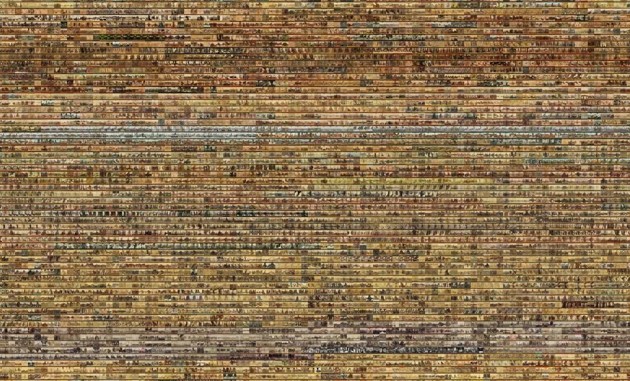

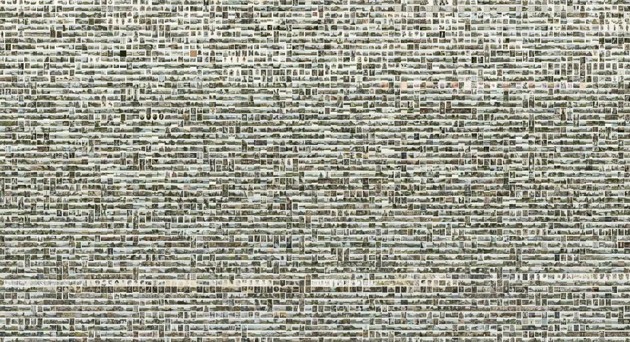

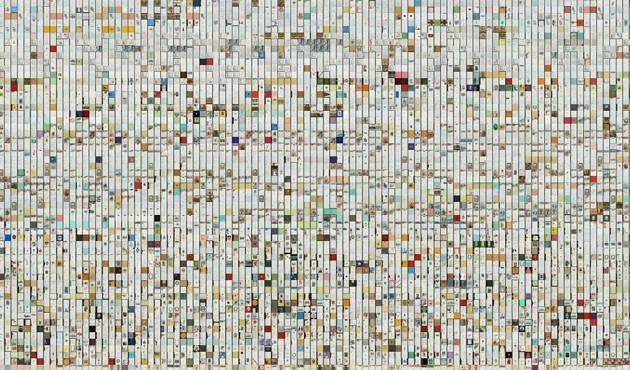

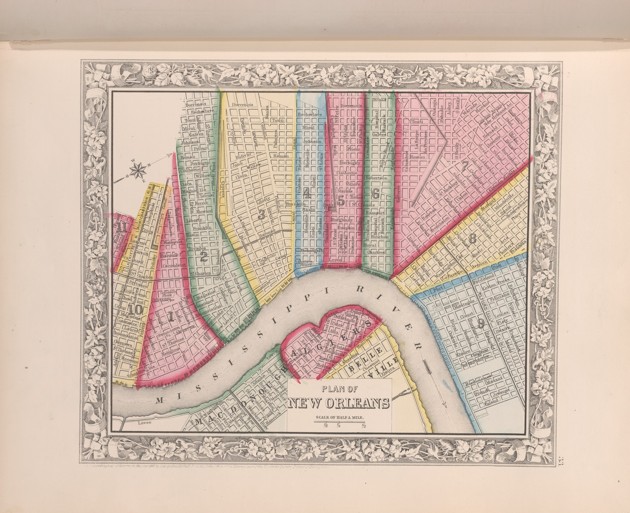

One of my favorite ways to explore the visualization is to sort images by “century created.” (The image above is sorted by type; it shows part of the huge collection of stereoscopic views.) You can see the beige and brown of 15th and 16th century documents give way to the grays of 17th century and 18th century illustrations, browns of 19th century photographs, and reds, blues, and yellows of bright prints and color photos in the 20th century.

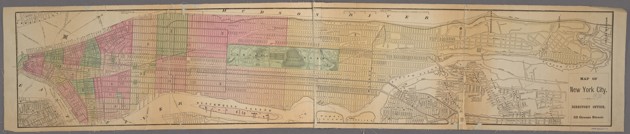

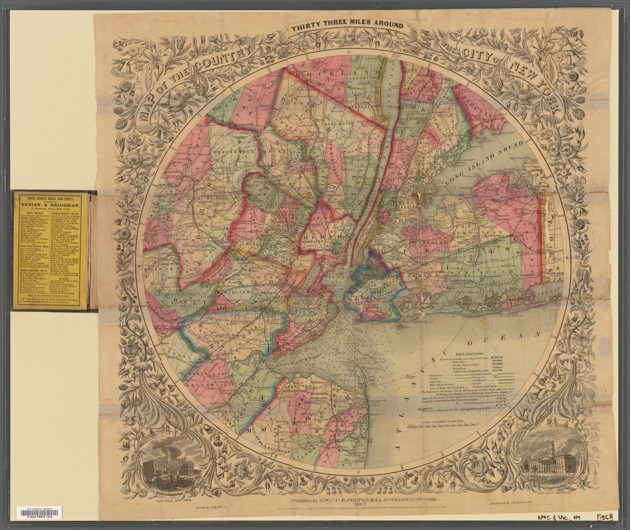

“The immediate and obvious takeaway is the sheer scale, especially given that this is still only a fraction—about one-fourth—of the total amount of digitized items online,” said Brian Foo, an applications developer in NYPL Labs and the creator of the visualization. “There’s a ton of stereoscopic views, old menus, old maps, old prints, old documents, all mostly this beige color. One of the motivations of doing this is that I wanted to see them all at once. I’m still exploring, and I hope we’ll be able to discover more things with more eyes on it.”

For this project, Foo divvied up images into five categories: title, images, dates, genres, collections. (He also collected a bunch of other metadata for people who want to take a deeper look at the collection.) The most challenging fields to work with were genre and date, Foo told me. “Similar materials could be described in many ways, and dates could be written in a variety of ways. There was still a lot of manual work to make the fields consistent.”

“The tricky thing about library data and this particular data set is that it was collected over decades and well before databases as we know them today existed,” Foo said. “The result is inconsistent data coming from a variety of sources in different formats.”

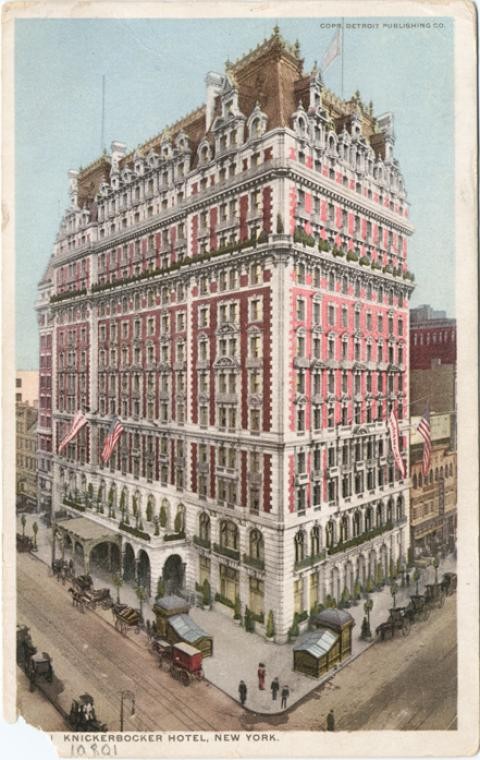

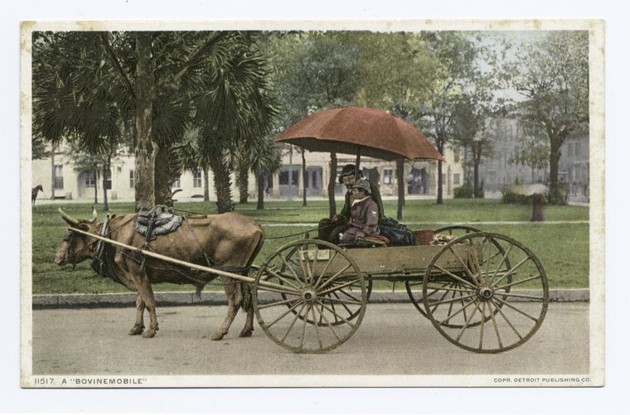

Among the many delights in this trove are menus for long-ago eaten banquets, postcards featuring buildings that no longer exist, gorgeous maps and engravings, yellowed photographs, elegant sheet music, colorful atlases, delicate etchings, bright cigarette cards, antique scrolls, and more.

Each category contains enough images to spend an afternoon or more in admiration. Don’t mind if I do.