Nearly 20 years ago, an idea came to Vice President Al Gore in a dream. He envisioned a satellite that would sit far out in space, nearly one percent of the way to the sun, consisting almost entirely of a camera and an antenna. The camera would capture an image of the fully sun-lit globe of Earth, a la the “Blue Marble.” The antenna would beam the image to Earth, where it could be seen live on the Internet.

That craft—nicknamed “Goresat”—never quite became a reality, but after a twisted, partisan, and decade-long path, its successor is now floating and operational those hundreds of thousands of miles away. The Deep Space Climate Observatory, or DSCOVR, principally monitors solar weather, but it also keeps one eye pointed back at Earth. And on Monday, NASA and NOAA began posting online the 11 photos it takes every day, about 36 hours after they are captured.

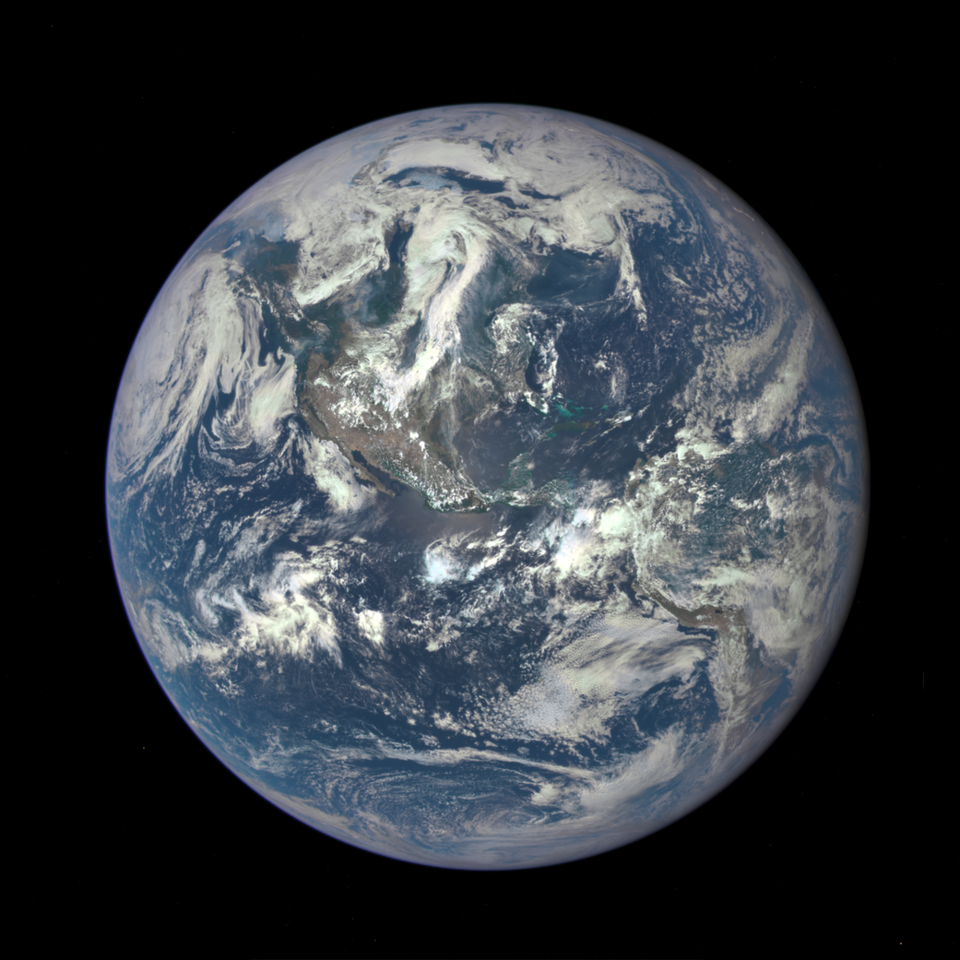

Here’s the Americas, midday on Saturday:

Since its release in 1972, the “Blue Marble” image has stood in for a kind of species-wide solidarity. As Gore told me when we talked in July: “It changed, that picture changed, the way we thought about ourselves and our relationship to the Earth.” The message of the “Blue Marble,” he said, is that “we all live on the same planet. We all face the same dangers and opportunities, we share the same responsibility for charting our course into the future.”

Yet the Blue Marble’s view of the Earth does not put all its regions in a planetary context.

As the Apollo 17 astronauts returned from the moon on December 7, 1972, they only saw part of Earth: Antarctica, southern Africa, and some of the Arabian Peninsula:

For more than 40 years, that was the only view of the Earth we had. While NASA imagery specialists merged many satellite images together to make a pseudo-“Blue Marble” in 2002, a composite cannot serve many of the same scientific uses as a single-frame shot. It’s bad, for instance, at measuring the comparative brightness and darkness of different regions.

So it was not until earlier this summer that we got a different taste of the Earth from afar. On July 6, 2015, DSCOVR snapped this photo of the Americas, the first view of a different collection of landforms. NASA and NOAA released it later that month.

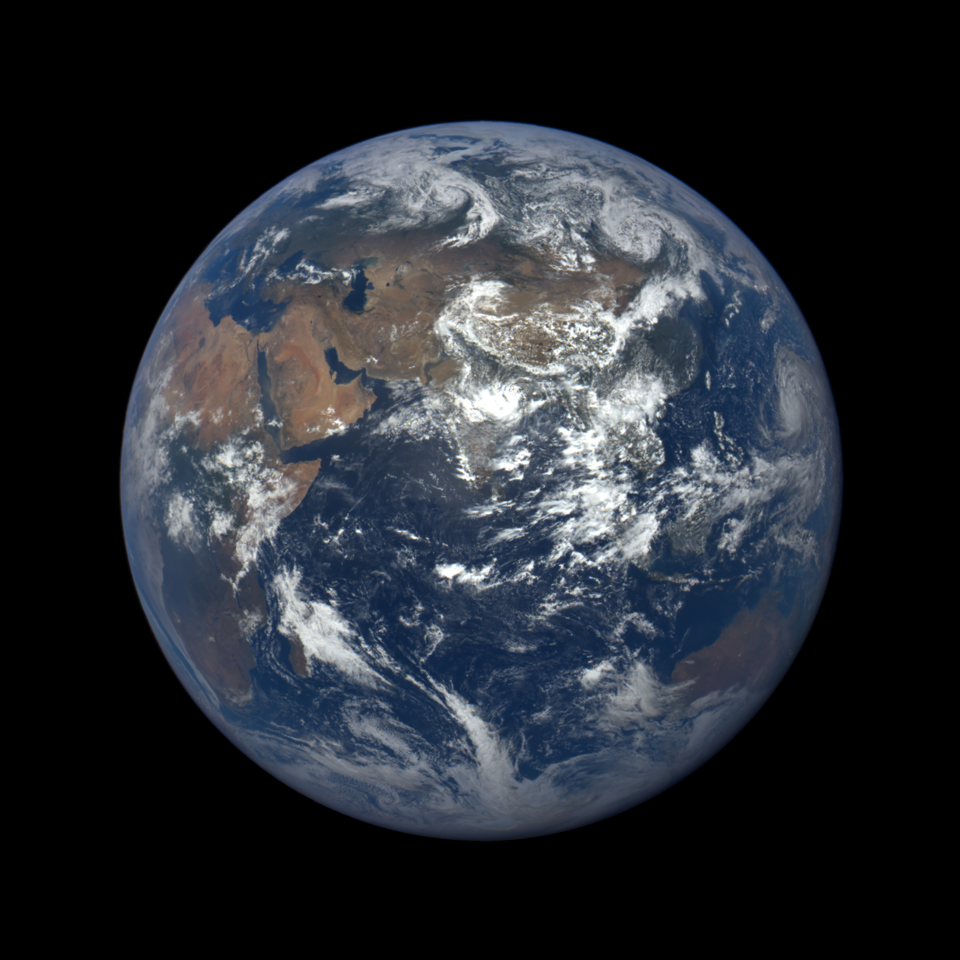

When DSCOVR’s archive was released to the public on Wednesday, many other Earthlings finally got a chance to see how their home is one among many. Below is the first “Blue Marble”-style image of China, Japan, Australia, and eastern Asia. It was captured on August 3, 2015, at 3:39 UTC.

Because DSCOVR sits at a stable point between Earth and the Sun, its photos always depict solar noon, or the couple of hours before or after it. Here’s midday in India and central Asia, captured on August 3, 2015. The subcontinent is near the peak of its monsoon season.

Europe, the Mediterranean basin, and northern Africa appear first in a July 25, 2015, image, captured at 10:52 UTC. You can even see Brazil jutting in, across the south Atlantic:

The Blue Marble is considered the single most reproduced photograph in history. It is universal in part because its subject is universal, but it was also ubiquitous for so long because images like it were so scarce. We only had the one.

Then, earlier this summer, we had two. And now every continent has been captured in its larger planetary context. As autumn turns to winter in the Northern Hemisphere, the planet will come to tilt up, and we’ll see more of South America and into Antarctica. As days lengthen again in the north, the antipodes will turn away from the sun and DSCOVR will capture more of the polar circle.

Since DSCOVR’s pictures will be so freely available online, I expect we’ll see Blue Marble-like images even more now. Developers will write scripts that auto-load the most recent image as a desktop backgrounds or phone-lock screen. Meteorologists will point to storm systems to prove their immensity:“And just look at how big this thing is from space, Tom.” And cable news channels (even them, alas) will figure out how to animate the pictures, and we’ll see a spinning Earth right before some anchor sends it to commercial.

But a photo that was once only a dream will become a commonplace. And in years to come, when discussing photos of the blue orb and the black abyss, we’ll talk about our favorites, not the firsts.