Jason Scott has something of a reputation. He’s a historian who works for the Internet Archive, and he’s known in some circles as the guy who can save bits of history right before they disappear.

So when he found out that a small store in Maryland that sold manuals for machinery was going out of business, and was going to get rid of its collection of nearly 200,000 obscure booklets in just a few days, Scott got to work.

He got to Maryland on a Friday to check out the stockpile at Manuals Plus. By Wednesday of the next week he had rallied over 70 volunteers to put together 1,600 boxes of manuals (nobody counted exactly how many booklets fill those boxes, but the guess is between 50,000 and 75,000) that now sit in three storage containers. The whole endeavor cost about $9,000, most of which was donated to the project.

Manuals Plus is in Finksburg, 30 miles northwest of Baltimore. The company is a relic from a time when a store of its kind was necessary. It specialized in electronic-test and measurement equipment—machines like oscilloscopes, multimeters, and video-test equipment. (Not only did Manuals Plus sell manuals, but it also installed cellphone towers and refurbished power tools.) “We maintain the World’s largest stock of previously owned original and reproduced, manufacturer-licensed, test-equipment manuals. If you're looking for manuals from Agilent, Hewlett-Packard - HP, Tektronix - TEK, Fluke, Wavetek, Wiltron, GenRad, IFR, Systron-Donner, or any of hundreds of others, you've come to the right place,” the store’s website boasts.

Nick Dawson purchased Manuals Plus, and the whole set of manuals, from the store’s previous owner about eight years ago, and moved its collection from Utah to Maryland.

Today, of course, the manuals business isn’t exactly booming. Those little booklets of information for how to troubleshoot or operate a new appliance are getting thinner, being replaced by CDs (which themselves are verging on obsolescence) and websites. Some time last year, Manuals Plus lost the lease to its building, and Dawson didn’t see a real reason to pay to shift all his manuals to a new facility. So he made plans to close up shop, told his long-time customers to make their final orders, and prepared to throw the manuals away.

Eventually, word of the closure trickled down to Scott.

“I’ve gained a reputation as someone you let know when things are going away,” Scott said. In the past, he’s helped connect people with books they’re about to throw away, then with archives that might take those books. But when he got the email about Manuals Plus, Scott says he was the last line of defense. So he drove 230 miles from his home in Hopewell Junction, New York, down to Finksburg, to find out if it was too late to help.

* * *

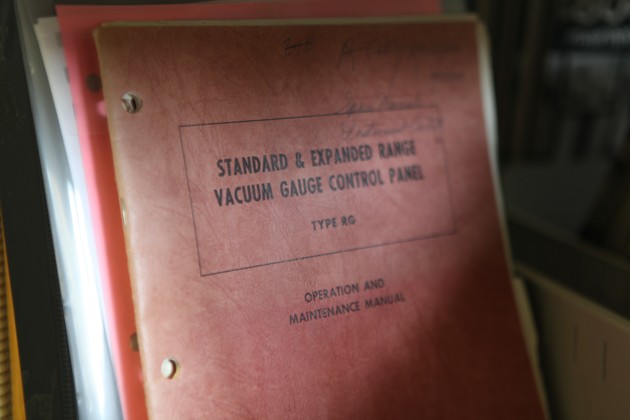

Manuals Plus’s warehouse takes up about five thousand square feet. When Scott first talked to Nick, he estimated that the whole shop contained “tens of thousands of manuals.” But when Scott got there on Friday to see the place, he said he was shocked by just how many books he was about to try to save. “They are relentlessly daunting. It’s a huge room, there were just books everywhere. It’s well put together but in every direction it’s manuals on shelves. We think it’s like 150,000 or 200,000 manuals,” he told me.

The plan wasn’t to save them all, just one copy of each unique manual. But even then, Scott estimated that would break the 20,000 mark. He told Dawson when he first arrived that he could probably gather those up in a week. Late that night, Scott detailed the mission on his blog. “It is 2 a.m. as I write this—I hope I don’t have to explain the inherent meaningfulness, usefulness, and importance of saving as many unique manuals from this collection as I can,” he wrote.

He asked for volunteers to come to Manuals Plus, and asked those who couldn’t come to donate money via Paypal. “This is a lot to take on. But when history’s at stake, it’s what has to be done.”

When Scott arrived at Manuals Plus to begin his work, two friends met him at the door, along with the 250 boxes they had ordered on Friday to put the manuals in. By the end of the day, about 40 people had come by to help.

Volunteers came from all over, Scott says. A whole family came through, a grandfather, daughter and granddaughter, who were all put to work. “There was one guy, he basically hitched a ride with a friend from Northern Virginia and went to this warehouse with no plan for where he was going to stay or how he was going to get home, just went and sorted manuals every day for three days. We had to shut the lights on him, he didn’t want to leave.”

The volunteers who showed up were given a host of different jobs: assembling boxes, stacking them when they were full, repacking boxes to maximize the efficient use of space, and combing through the stacks and pull out unique examples of manuals—a task that was a bit harder than anybody expected.

First, you can’t tell whether two manuals are the same from looking at their spine, Scott says. They both might say 1080B on the spine, but one could be revision C, while the other is revision B. So each manual has to be inspected thoroughly. And while there was some general order to the manuals, in the eight years that Manuals Plus existed, their stacks had blossomed with quirks. When they ran out of space on one shelf for something, books would go wherever there was extra space. Duplicates were scattered across the room. These idiosyncrasies compounded the challenge of figuring out which books were unique and which were duplicates.

Eventually, it became clear that the 250 boxes they had ordered wouldn’t be enough, so they ordered 1,000 more. Then, on Tuesday, Scott realized even that wasn’t enough, so volunteers went out to Costco and Staples to buy more. In the end, with the help of about 70 volunteers, they packed up 1,600 boxes worth of manuals and shipped them to three storage units nearby. Even then, Scott says he’s sure they missed some manuals, and got too many of others. “We had three days. The right thing to do was spend two and a half months.”

Scott says that he wants to correct a common misconception about why he did this. He doesn’t care about engineering, or the machines that these manuals went to. “I never went to school for engineering. I have no idea what these are, I don’t know three-quarters of these companies. I didn’t save it because I was like, ‘Yay! My hoard will get bigger,’” he said. He saved the collection because it was going to disappear.

And now that he’s had a little time to go through and look at some of the manuals they saved, Scott says he’s finding a deep appreciation for these little booklets. “There’s value and meaning here,” he says. “Everything from the fonts and the layouts... How a company presents its brand, how it appraises things. And other times you pick one up and, wow, nobody writes with this brilliance and clarity about technical subjects. These manuals feel like they’re a project as important as the item they’re describing.”

* * *

So what does an archivist who doesn’t care about engineering do with over 50,000 engineering manuals?

The first step is to go through and figure out exactly what’s in the collection, then sort the manuals by vendor. After that, he and his colleagues will start figuring out who might want to take some of these old booklets. “Some of them will go to archives, there are certain archives that will want some things. Nobody wants all of them,” he says. At the same time, since Scott works for the Internet Archive, his natural inclination is to start scanning them. He’s already talked with Internet Archive scanning centers to figure out whether they could have some of the manuals uploaded online.

But Scott says he wants to be careful with his digitization efforts. Just like Manuals Plus struggled to make ends meet selling manuals, there are a host of other mom-and-pop manual stores out there. Scott worries that if he simply scans all these and plops them up online, he could actually put people out of business. “I don’t want to crush anybody,” he says. So he’ll start by scanning manuals that are easy to find, or that nobody needs anymore. “I’m very new in this area, this is not an area I was involved in in any real significant way until three weeks ago, and now I’m a major player, and I want to figure out what to do next with it that’s both responsible and helpful.”

“It was very exhilarating to go from a strong feeling to getting a bunch of people together to save something. I have to parlay that into a more robust and organized thing.” So he’s decided to try and see how this kind of salvage project might work as an organization.

They’re calling it Archive Corps. One of the volunteers registered the domain for Scott, and the idea is that if something needs saving, dedicated Archive Corps volunteers could mobilize to do so—whether it’s a manual store in Maryland, a warehouse in Nevada, or a library in Canada.

When he first put out a call for help saving the manuals, Scott says he got about 200 emails from people interested in volunteering. So in the future, when something is in danger of disappearing, Scott won’t be the only one to call. He might have a whole network of lieutenant archivists to mobilize. “People can come together and say, ‘Oh, this is a beautiful one time thing,’ or you can say, ‘This could be an organization.’ So let’s take a shot at it.”

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/09/introducing-the-archive-corps/403135/