Ice mountains as tall as the Rockies loom high above Pluto’s surface. They are made of frozen water, and they rise from the planet’s methane and nitrogen surface. About every 150 hours, a brilliant star rises from behind them. The star is no larger than a dot—not really bigger than any pinprick in the sky—but it shines with the brightness of ten thousand full moons.

Good morning, Pluto.

* * *

On Wednesday, NASA scientists announced the very first images and findings captured by the agency’s New Horizons probe. The spacecraft completed a gravitational dance with the tiny world and its moon, Charon, on Tuesday morning, but it was so occupied with observing the two orbs that it only began beaming back the very first and most compressed images hours later.

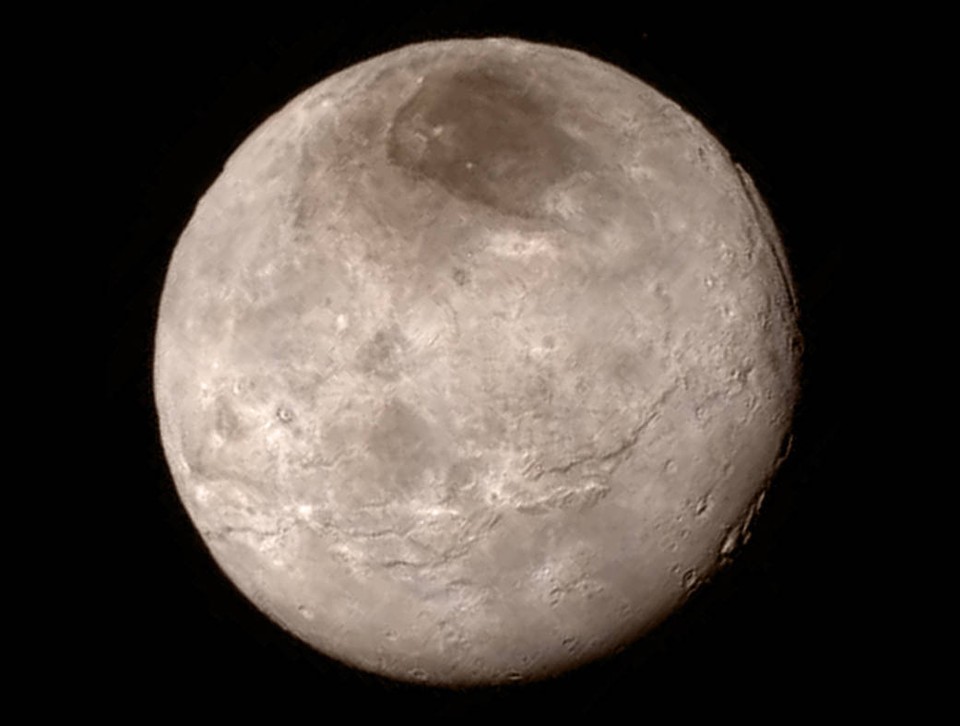

NASA released two historic new images. The first is the highest-resolution photo of Charon ever, capturing the full disk of the moon. The second is a close-up on Pluto’s surface. Both were full of surprises: It was the kind of press conference where giddy scientists chuckle and repeat, “I don’t know” over and over again.

Both images were also very, very exciting. One suggests a new understanding of how geology might work on the universe’s many small, icy objects.

Charon has some but not many craters. Scientists would expect to see many on its surface. The lack of them suggests that evidence of previous asteroid collisions has been erased by changes on the moon’s surface—by, in other words, geological activity.

The findings on Pluto were more surprising. The image captured by LORRI, the high-resolution imager aboard New Horizons, captured a swatch of territory hundreds of miles wide.

(For reference, the patch includes some of the bottom of the enormous heart-shaped marking on the planet’s surface that was first observed on Tuesday. NASA has informally been dubbed the heart “the Tombaugh Reggio,” after Clyde Tombaugh, who discovered the dwarf planet in 1930.)

There were zero craters in the newly observed region. Again, scientists would expect to see many of them—the complete lack indicates that Pluto is almost certainly geologically active. And that throws entire ideas of how space rocks work into question.

Pluto is the first small, icy world that humankind has closely observed that isn’t orbiting a much larger planet, like Neptune or Saturn. Moons attached to a large planet might be subject to tidal heating, where the force of the giant’s gravity deforms and heats the smaller one. Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, is geologically active—it has volcanoes and surface change—and scientists hypothesized that the giant blue planet might be heating it up.

There’s only one problem. “This doesn’t look like Triton, which up to now is what we thought was the most similar object in the solar system to Pluto,” said Alan Stern, the principal investigator on the New Horizons mission, in a press conference about the findings.

But Pluto is geologically active without tidal heating. Its energy (and likely Charon’s too, for that matter) must be coming from somewhere, but scientists aren’t sure where yet. In the press conference, they hypothesized that this might be due to radioactive energy building up inside the planet. Pluto might also hide a vast, frozen ocean inside it, which might be gradually melting and expanding the surface.

We just don’t know.

“I would never have believed that the first close-up shot of Pluto didn't have a single impact crater on it,” said John Spencer, a space scientist at the Southwest Research Institute. “There’s something very different about Plutonian geology.”

And that, in turn, is important, because humanity’s search for exoplanets—planets beyond the solar system—has just begun. So far, we’ve found 1,932 of them. Some are gas giants, a few seem to be rocky worlds in their star’s habitable zone. What seems likely, though, is that there are many worlds like Pluto: small, smaller than planets even, and distant from the sun.

If all those objects are geologically active, we might be living in a far more active universe than we thought. Suddenly, the many thousands of small objects beyond Neptune look like they could have cryovolcanoes on them, too. The universe might have many more volcanoes and earthquakes than we thought.

“I know we’ve tend to think of those worlds, types of objects, as candy-coated lumps of ice, and I think they could be equally amazing if we ever get a spacecraft there,” said Spencer.

It will take many years before scientists understand the full import of the science that New Horizons did on Tuesday. The images received on Wednesday were heavily compressed. It will be more than a year until NASA receives the full raw data set. But on Wednesday, scientists seemed exhausted, surprised, and overjoyed.

“Pluto is something wonderful,” said Stern. “This is what we came for.”

Cathy Olkin, another lead scientist with the program, added: “This exceeds what we came for.”

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/07/new-horizons-nasa-ice-mountains-of-pluto-geological-activity/398687/