In a sprawling two-hour-long keynote at its annual developer’s conference, executives from the world’s most valuable company touched upon as many of its business commitments as they could.

They outlined upcoming changes to its desktop, mobile, and wearable operating systems. They celebrated the 100-billionth app downloaded from its App Store. They detailed the expansion of Apple’s proprietary payment system.

And they unveiled a new music service, Apple Music, which the company hopes will compete with the likes of Spotify and Pandora.

Apple Music is the real news from the event, as it’s a bonafide new product. (Though iPhone users will appreciate some software updates coming this fall, including a power-saving mode and a map with public-transit data.)

The company really announced three music-related services on Monday, all glommed together. The first is Apple Music, proper, which is a streaming service like Spotify or Rdio (or like Netflix, but for music). It will let users search for songs, listen to them, and arrange them into playlists. The second is BeatsOne, an Internet radio service with DJs that Apple has poached from major terrestrial stations. The third is Artist Connect, which lets users “connect” with musicians.

Artist Connect is the least interesting of these. It seems like a plain old topic page where artists can upload photos, video, and music. It’s a set of musician-themed content buckets, in other words, like an old-school Myspace or a Facebook fan page.

BeatsOne and Apple Music, though: They’re more compelling.

Apple is getting into streaming because it shows all the signs of a business on the rise. Subscription services saw 39 percent growth in 2014 compared with the year before. During the same time, revenue from MP3 downloads—which is where Apple makes its money in music—fell 8 percent. (These stats come from the 2015 trade report of the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, the source of record on this sort of stuff.)

And Apple’s corporate health doesn’t depend on selling music, per se. Only about 10 percent of its revenue comes from “iTunes software and services.” The global business of selling MP3s, likewise, remains robust: “Permanent MP3 downloads” still constitute more than half of all digital-music revenue worldwide. But the various trends don’t exactly look good, and it makes sense that Apple would like to protect its stake in the market.

In other words, Apple is entering the streaming business for defensive, not offensive, reasons.

This could work! There are hundreds of millions of iPhone users wandering around the planet, and many of them will want to try out a new Apple music product. But this sets up a very different environment than Apple’s previous entries into music. While the company’s rise over the past two decades has been powered by consistency—it offers a well-designed product that, at least in theory, “just works”—it has been spurred by two great advancements since the iPod. The first of these was combining an MP3 player, the iPod, with an online music store which let users buy songs easily, cheaply, and independently of albums. (The second of these was the iPhone, the first true pocket computer, and in many ways the economic cornerstone of the modern app economy.)

Apple Music, at least the version that was announced Monday, is not a revolution on the order of the iTunes Store. Apple isn’t offering something unprecedented; they’re selling design-y Spotify. If it prevails, Apple will introduce an untapped market of millions to the joys of online streaming music. Or it could look like iTunes Ping, a music-themed social network introduced by the company in 2010 that barely survived two years.

They’re banking on its scale, in other words. Apple Music will not succeed because of Millennials already hip to Spotify. It will succeed because of the vast, less-hip population. It will succeed, in part, because of its appeal to dads.

Apple has always had a hint of dad-liness. It made a U2-themed iPod, then a decade later downloaded a new U2 album to every iPhone or computer without asking first. It ran nationwide ads to celebrate the introduction of the Beatles to the iTunes Store. And now it really, really wants to tell you about its new watch.

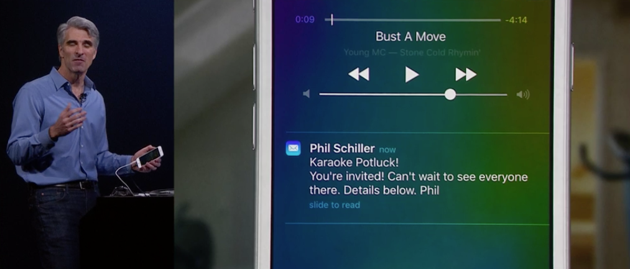

Monday was the first time in years that female Apple executives appeared onstage at one of the company’s events. (They were Jennifer Bailey, who leads Apple Pay, and Susan Prescott, who introduced its new News app.) But the overall tone of the keynote carried forth the dad mystique. Bruce Springsteen and John Lennon were both referenced repeatedly. There was a running joke about all the Apple executives planning a potluck karaoke together. (Which, first of all: What is that? And second: What’s more dad than that?)

But Monday’s announcement offered few novel features. Its interface seems confused. It has a DJ-driven radio element, despite the fact that Apple’s first foray with music, the iPod, succeeded because its logic was counter to the portable radio. And it costs $10 per month.* (The family version is $15—that’s almost as much as The Wall Street Journal.)

The most popular streaming service, Spotify, has 60 million users but only 15 million paying subscribers. It isn’t profitable. But it has something Apple Music doesn’t: a free tier.

So Apple isn’t entering streaming because it has some brilliant insight about the nature of digital music or some new, hard-won concession secured from record companies. It’s entering because it’s so big it might still win. It’s the strategy of empires. We’ll see if it works.

* This article originally stated that all Apple Music subscriptions cost $15. We regret the error.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/06/apple-streaming-music-service/395378/