A warning from Edward Clarke, M.D., a professor at Harvard: "There have been instances, and I have seen such, of females... graduated from school or college excellent scholars, but with undeveloped ovaries. Later they married, and were sterile."

He goes on to explain how reproductive organs fail to thrive.

The system never does two things well at the same time. The muscles [note: muscles = menstruation] and the brain cannot functionate in their best way at the same moment.

These passages are from Clarke’s book, Sex in Education; or, A Fair Chance For Girls, published in 1873. The gist: Exerting oneself while on the rag is dangerous. Therefore educating women is dangerous. For a woman’s own safety, she should not pursue higher education. The womb is at stake.

Clik here to view.

Today, it’s easy to write off Clarke’s thesis as one doctor’s nutty ramblings. His descriptions of students—“crowds of pale, bloodless female faces, that suggest consumption, scrofula, anemia, and neuralgia,” as a result of “our present system of educating girls”—sounds more like The Walking Dead than students at a university campus. But when A Fair Chance for Girls was published, administrators and faculty opposed to women in education hoisted up the book as a confirmation of their views, couched in an argument about safety.

Mary Putnam Jacobi thought the whole thing was hogwash. Jacobi, an American, was the first woman admitted to France’s École de Médecine. It took a bit of wrangling, but once she was in, Jacobi found her medical training thrilling. Certainly there were people who doubted her ability to succeed—even her mother did some hand-wringing over her schooling—but Jacobi proceeded with ease and humor. In 1867, she wrote home to assure her mother, “I really am only enjoying myself... the hospitals present so much that is stimulating, (and do not be shocked if I add amusing) that I am never conscious of the slightest head strain.”

To battle Clarke’s assertions, Jacobi could have presented her personal experience as a counterargument. Her education at the École de Médecine took place after she’d already received an M.D. in the United States. Medical school made Jacobi neither ill nor infertile. But bringing forward an autobiographical account when evidence was within reach was like feeling for your own heartbeat when it could be measured with a stethoscope.

Jacobi challenged Clarke’s thinly veiled justification for discrimination with 232 pages of hard numbers, charts, and analysis. She gathered survey results covering a woman’s monthly pain, cycle length, daily exercise, and education along with physiological indicators like pulse, rectal temperature, and ounces of urine. To really bring her argument home, Jacobi had test subjects undergo muscle strength tests before, during, and after menstruation. The paper was almost painfully evenhanded. Her scientific method-supported mic drop: “There is nothing in the nature of menstruation to imply the necessity, or even the desirability, of rest.” If women suffered from consumption, scrofula, anemia, and neuralgia, it wasn’t, as Clarke claimed, because they studied too hard.

Her study—sweeter for its evidence than its tone—won the Boylston Prize at Harvard University just three years after Clarke, a professor at the same school, published A Fair Chance. The Clarke versus Jacobi scholarly disagreement may sound like academic quibbling, a biased doctor against a rigorous one, but in the argument over who was allowed university admission, to have science on your side was hugely important. After Clarke’s paper fortified university walls, Jacobi systematically dismantled the barrier. Her paper was greatly influential in helping women gain opportunities in higher education—especially in the sciences.

Jacobi had wanted to be a doctor since childhood. “I began my medical studies when I was about 9 years old,” she remembered. “I found a big dead rat and the thought occurred to me that if I had the courage, I could cut that rat open and could find his heart which I greatly longed to see... my courage failed me.” Although she tabled the exploratory surgery until she was trained to do it, her interest in the body never waned. In the meantime, Jacobi wrote. Growing up in a family of well-known book publishers, she dabbled in her family’s business, placing stories in The Atlantic starting at age 15 and later in the New-York Evening Post.

Jacobi’s father wasn’t thrilled to hear she’d decided to attend medical school. In response, he dangled the amount of her university tuition before her, a carrot that would be hers should she decide against higher education. Jacobi declined his offer, leaving for the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, in the early 1860s before continuing on to Paris for a second round of schooling. When her mother wrote requesting an update, Jacobi replied, “I think you are rather naive to ask me if ‘I meet many educated French ladies who are physicians.’ Such a thing was never heard of.”

In Paris, an American was considered enough of a curiosity that after months of lobbying, Jacobi was able to claim the first spot at the École de Médecine ever awarded to a woman. There were a few stipulations attached to her attendance. She had to enter lectures through a door not used by other students and sit near the professor. Jacobi joked that hers would be the first petticoat the school had seen since its founding. However strange the circumstances, Jacobi found assimilation easy. She wrote, “I... feel as much at home as if I had been there all my life.”

Upon returning to the United States after five years in Paris, Jacobi began lecturing at Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, practicing medicine and carving out more opportunities for women in the field concurrently. Jacobi helped found the Women’s Medical Association of New York City in 1872, opened New York Infirmary’s children’s ward, and became the Academy of Medicine’s first female member.

When she was diagnosed with a brain tumor, Jacobi documented the symptoms just as thoroughly and objectively as if she were responding to Clarke’s ridiculous claims. She titled the result, “Description of the Early Symptoms of the Meningeal Tumor Compressing the Cerebellum. From Which the Writer Died. Written by Herself.”

Jacobi did like to get in the last word.

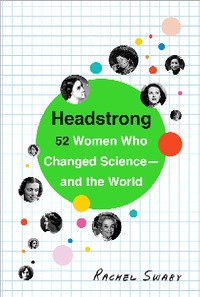

This article has been excerpted from Rachel Swaby's forthcoming book, Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science – and the World.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/04/getting-educated-does-not-make-women-infertile-and-other-discoveries-made-in-the-1880s/389922/

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.