Chinua Achebe, the celebrated Nigerian author of Things Fall Apart, died at the age of 82 in 2013. But to social media, he only passed away this weekend. People began tweeting condolences (or re-condolences) Sunday night, writing "RIP" and "another one gone" and sharing the New York Times obituary from two years ago.

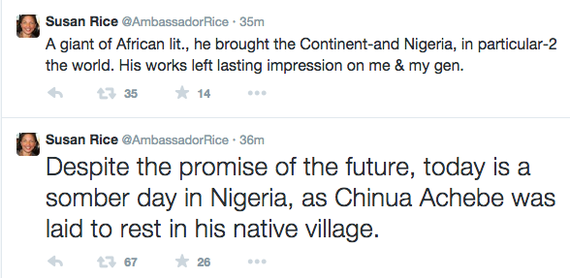

The re-mourning of Achebe spread far enough online to eventually reach high-profile users like the White House national-security advisor Susan Rice, who chimed in Monday morning with her own tweets:

When others pointed out the error, Rice deleted her tweets, later posting:

Any occasion to remember the life & legacy of one of Africa’s greats, Chinua Achebe, is worth noting (+ a good reminder to read fine print!)

— Susan Rice (@AmbassadorRice) March 23, 2015 It wasn't just Rice who missed the fine print—the "news" duped plenty of people. So what happened? As Nieman Lab's Joshua Benton pointed out, someone likely posted a remembrance of Achebe's death and recirculated the New York Times obit. Others, seeing the headline and not the timestamp, believed Achebe to have just died, so they fell victim to "reflex sharing," as the First Post put it. It wasn't a hoax, just an Internet-assisted ripple effect.

And that ripple effect happened because social media is, Benton wrote, "unstuck in time," where old material can be recycled digitally to seem new, where what's trending no longer means what's most recent. Just look at Facebook's "Trending" news sidebar, which doesn't include timestamps until you click through to look at individual stories. Scroll through the social-media feeds of online publications (including The Atlantic), and you'll find plenty of repurposed and re-promoted archival content. Stare at a Twitter feed long enough, and the same stories will reappear over the course of a day, no updates necessary.

There's some irony in the fact that, in the age of real-time news, time is losing its grip as one of the crucial factors in determining newsworthiness. (It still matters, just in a different way.) Readers don't always look at the date and the time of a story, because there's no association between the story and the time they see it. When in the past, people physically picked up newspapers from their doorsteps at a certain hour during the day (or tuned into TV networks for nightly news), today, the same information is presented to them online not as headlines, but as topics, transformed into key words transformed further into hashtags. The notion of timestamps associated with individual stories can seem, well, outdated. And as news organizations increasingly rely on social networks (mostly Facebook) to circulate their stories, the news ecosystem incentivizes keeping timestamps somewhat hidden.

So, in that sense, Rice and those fooled by the revived news of Achebe's death simply did what social media has conditioned them to do: They shared, because if everyone was sharing, it meant it was news. As the First Post put it:

We're pretty sure that a lot of the people who shared the NYT link and beat their social-media chests with grief today had most likely done the same two years ago when he really passed away—and just forgotten about it. In the endless river of RIPs, it is easy to lose track those you have so loudly mourned on your TL. And while a section of people who did remember that Achebe had died two years ago may snigger at their timelines in superior fashion, the truth is that this phenomenon says something about all of us and the way we are evolving to respond to the constant flow of information that comes to us via the Internet.

All news stories, breaking or otherwise, have become news without expiration dates. Readers, not just publishers, help decide when something falls out of the news cycle. Maybe that's why the few exceptions with finite life cycles can be so captivating. Think of the llama drama, for example, or #TheDress—those stories and others like them can only be talked about for so long. ...Or not.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/03/on-social-media-everything-happens-all-the-time/388469/