The Natural History Museum in London has a gargantuan task ahead: the mass digitization of its sprawling collections. Over the next five years, the museum plans to scan more than 20 million pinned specimens. The job will require imaging an inordinate variety of insects, from metallic-green beetles and butterflies as colorful as a Monet, to tropical parasitic wasps and grasshoppers from Mount Everest.

But photographing tiny bugs can be tricky. Meaningful images must capture minutiae such as leg hairs, wing tips, and antennae. And gathering those details is challenging for museum researchers dealing with fragile specimens, some of which are more than 300 years old. “Every time you pick one of these up on a pin, there’s a chance they will break because they are very brittle,” said Steen Dupont, an entomologist at the museum. “But we still want to image the insects to make them available.”

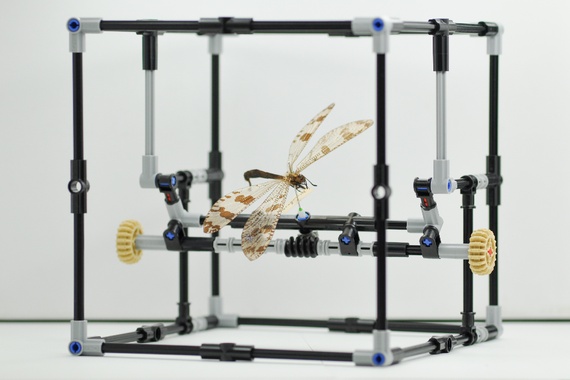

Though there are several commercial devices that allow entomologists to manipulate pinned insects without touching them, most are often bulky and expensive. Dupont wanted something that was cheap, portable, and customizable so that he could observe the wings of his moths easier. So he turned to Legos, his favorite childhood toy, to construct something new. From the black and grey building blocks and connectors he crafted several insect manipulators called “IMps” that can position and rotate pinned specimens for imaging and 3-D modeling. (The name is inspired by imps, the mischievous assistants to warlocks and witches, whom Dupont called the academics of the mythological world.)

“There’s no view you cannot get with the manipulator, which is cool,” he said. “It’s a working prototype. It’s good; it’s durable, and really cheap. You can order its pieces from anyplace in the world, and anybody can build it.” Step-by-step instructions to construct his designs were published and made freely downloadable this month in the journal Zookeys.

The smallest of his models only contain about 30 pieces according to Dupont. The largest design has more than 150, but takes about 10 minutes to construct. Most of his manipulators are small enough to fit underneath a microscope, and some can be outfitted with mobile phones capable of taking pictures.

Dupont first decided to create a new viewing device while completing his doctorate degree in Copenhagen after watching his friend struggle to photograph a pinned specimen beneath a viewing cup. “Seeing him take this cup, and reposition the insect every time he had to take a picture drove me crazy,” he said. “I saw a problem that I could tinker with.” He started designing metal insect manipulators, but found them to still be quite cumbersome.

It wasn’t until he moved to London that he began to incorporate the Legos into his science. “I’m Danish, and Danish people are very proud of their Lego, and I grew up playing with Legos,” he said. And after leaving Denmark, where Lego is headquartered, he became homesick and started to latch onto things that reminded him of home. Soon he amassed a large collection of the building blocks and decided with his new colleagues to again tackle the problem of imaging fragile insects. The response, he says, has been overwhelming. “I already have several colleagues who’ve stolen their kids' Legos and posted their designs with the pieces online.”

One colleague, Ian Owens, the director of science at The Natural History Museum, London, says he's a big fan of the Lego insect manipulator, and likes how it may help people think differently about digitizing natural history. He also noted that almost half of the people who help digitize global natural history collections are “expert-amateurs” who do not have access to the expensive institutional devices. “[Dupont and colleagues] are very keen on finding ways of lowering the hurdle to let people help digitally.”

Across the ocean at the Smithsonian, the curator Jonathan Coddington said that he, too, is impressed by the device, but more so by its flexibility than its price tag. “It’s not so much in lowering the cost as it is having a machine that can do whatever you need it to do.” The Smithsonian has completed several massive digitization projects of their own, including scanning 40,000 bumblebees in 40 days. “This gizmo is the latest in a long series of things that scientists and technicians invent to do their work,” he said. “This one’s cool.”

Dupont said that his next steps are to find an easy way to add a light source to the design. He also wants to combine the Legos with robotics to automate the picture-taking process. He says new solutions pop into his head every time he stumbles upon a piece in his collection that he previously thought he had no use for. “It’s especially fun if there’s a tinkering problem to be solved,” he said. “I love doing that.”

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/02/solving-a-museums-insect-problem-with-legos/385380/