Green slime is that gooey non-Newtonian fluid you may remember from childhood science experiments or Nickelodeon television shows. It’s fluorescent, somehow sticky and springy at the same time, and looks like snot. In our wild imaginings, it becomes toxic or radioactive. It’s just as likely to have come from outer space as it is to have emerged from the deep sea. If green slime had a smell, it’d be rotten eggs. If green slime made a noise, it’d be a long, wet burp.

This plaything has a naturally occurring counterpart—an ancient life form of single-celled amoebas that incubate in the soil and have the capacity to band together to find food. Green slime takes some of the otherworldliness of its natural cousins and packages it for sale.

What is it about these green blobs has earned them a place in the pantheon of American childhood objects?

In the 1970s, British anthropologist Allison James seized upon the word “ket,” which was used by adults and children alike to describe the kinds of sweets that kids ate but grown-ups would (almost) never touch. She became fascinated by this class of cheap, “rubbish” foods, and cataloged their various outrageous qualities: saturated colors, extreme hardness or gumminess, sour or fizzy qualities upon the tongue, absurd names. (Our present-day equivalents to the British candies of the 1970s would be Gobstoppers, Warheads, Airheads, and Gummy Worms.)

For James, the intense interest that her study’s young participants had in ket—the hoarding, the passionate debates on the merits of various types, the sharing and trading—was a way for children to establish a difference between themselves and adults. Kids have little agency in the world, but liking ket gives them some. The concept of ket is helpful when you’re trying to understand any number of things, food and non-food, that thrive in kids’ culture but that adults find disgusting, rude, cheap, or aggravating. Goosebumps books are ket. The off-brand toys you used to buy off the supermarket rack are ket. Barney is ket. Harry Potter is not ket; those Harry Potter earwax jellybeans might be.

Considered from some perspectives, green slime is simple ket. It’s a material that has no function other than to entertain. It’s symbolic. It’s disposable (though you should not flush it down the drain!). It often functions in kids’ narratives as an anti-adult agent, bringing with it a joyful anarchy that disrupts the careful scheduling of grown-up days. But in the depths of each glob are embodied all the contradictions of contemporary kid culture.

Green slime is a sanctioned, commodified, profitable mess. Packaged in a toy store, it’s rebellion that’s sold by the gooey ounce. But you may also find it in science instruction—an indication of how hard teachers are trying to “relate” science to kids’ media lives. And when made at home, it’s a parent’s attempt to reinsert some of the sensory feeling of being outdoors into lives increasingly circumscribed by walls.

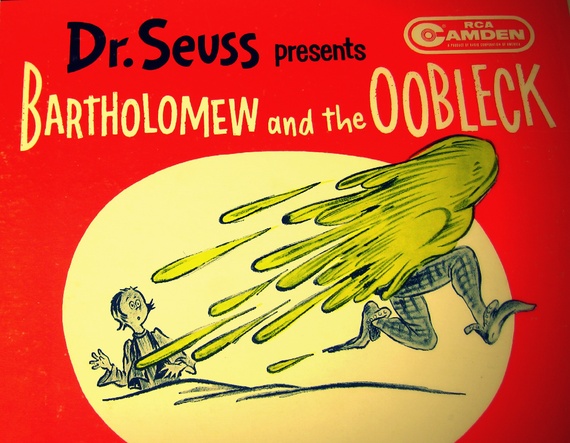

Dr. Seuss’ 1949 book Bartholomew and the Oobleck is perhaps the first appearance of a slime-like substance in children’s literature. In the story, a king gets bored of all of the other substances that come out of the sky, and asks his magicians to make something new. The “oobleck” that descends threatens the harmony of the kingdom.

Early precursors aside, no bit of kids' culture has more wholeheartedly cleaved unto the messy, anarchic qualities of slime than Nickelodeon. Nickelodeon, the kids’ network founded in 1979 that has profited from the increasing penetration of cable into American households, had a big hit in the early 1980s with You Can’t Do That On Television. On this Canadian sketch comedy show that first aired in the United States in 1981, saying the words “I don’t know” would trigger a “sliming.” Buckets of green slime would fall from the sky, drenching the unfortunate actor.

Nickelodeon recognized the popularity of the You Can’t Do That On Television slimings, and integrated the idea into the trivia game show Double Dare, which first aired in 1986. On Double Dare, contestants who couldn’t answer a question could opt to instead compete in a “physical challenge” that often involved messy substances such as shaving cream, creamed corn, chocolate syrup, and green slime itself, being used as a weapon or an obstacle. Slime showed up on Nickelodeon’s game shows Finders Keepers, Think Fast, and Wild and Crazy Kids, as well as off-network imitators like Fun House and the short-lived Slime Time.

Slime became emblematic of the Nickelodeon brand and the network even incorporated an orange, slime-like splat into its logo. The amorphous blob, tossed at characters from shows or at the logo itself, showed up in animated network identification bumpers as well. Sliming was democratic, free, fun. In its very essence, slime was symbolic of something happening that was “Just For Kids!” Slimings of public figures like Steven Spielberg or Harrison Ford at the annual Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards emphasized the material’s disruptive qualities. Covered in green, adult celebrities had to play along with the game, smiling for their young audiences.

Slime flowed its way through the toy stores of the 70s, 80s, and 90s, gathering dollars for Mattel, Nickelodeon, and Kenner. The packaged substance is a gel made from guar gum, a stabilizer and thickening agent familiar to consumers from many food and cosmetics labels. Sodium borate—commercially sold as Borax—serves as a cross-linker, binding together chains of polymers so that the substance can flow and stretch. (David Katz, a chemist and educator, has a longer explanation of the science here.)

Some variation of this compound was first sold as Mattel’s Slime in the late 1970s, and as “Nickelodeon Green Slime” in the 80s and 90s. Often, the Slime came in a barrel, reinforcing the implied relationship with toxic waste. Later, Nickelodeon sold a slightly less pourable compound, Gak, that made a rude farting noise when it was squished back into its container, thereby combining two objectionable qualities of ket—texture and sound—in one toy.

Other 80s franchises sold variations on slime, some of which were supposed to be used in conjunction with plastic toys. He-Man had Evil Horde Slime Pit, Ghostbusters’ ghosts left gooey trails of Ecto-Plazm, and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were born from Retromutagen Ooze. Less brand-conscious ket makers went off-license, offering edible slime: the Hose Nose, which you strap to your face and trigger with your tongue to let “candy slime” fall out, and Slime Slurps, which combined the grossout factors of slime and insects.

Nickelodeon integrated green slime across its product lines, selling green slime-branded shampoo, Green Slime Ice Pops, and licensed its trademark to Burger King for a “slime” dipping sauce (which was, disgustingly, apple-flavored). In 1990, the Green Slime Geyser was unveiled in the Nickelodeon section of Universal Studios, Florida. The attraction invited people to watch a machine that occasionally emitted an Old Faithful of goo. Journalist Charles P. Pierce visited the theme park one day in 1995 and reported that a tour took a group through the “kitchen” where slime and Gak are, allegedly, brewed:

There, a nice woman explains that, while slime is just, well, slime, Gak is slime with certain additives. “For example,” she says, “a nice, juicy booger.” The children erupt into a chorus of mock vomiting. The parents, who have already been dragged through all manner of pop culture gimcrackery elsewhere on the lot, look as though someone has collectively hit them on the head with a hammer.

And, indeed, slime seemed to provoke parental disapproval in real life, not just by implication. Posters on a message board for collectors of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles toys, while discussing the possibility of finding unopened canisters of Mutagen Ooze (now selling for up to $20 a pop), compare notes as to whether their mothers would allow them to have it when they were younger. “My mom said the same thing about it ‘staining the carpets’!” one moaned, while another added, still bitter, “We were IN THE CHECKOUT at toys r us and some lady told my mom about the staining and she put it back on the shelf right there. GRRRRRRRRR.”

Since Nickelodeon gave slime its commercial spotlight, the substance has begun showing up in popular science books for children. These have become, in recent decades, increasingly focused on selling science as a way that experimentation can challenge adult sensibilities. The emotional aesthetic of these books casts science as an oppositional practice, something that, like other bits of kids’ culture, adults just wouldn’t understand.

This is a new angle. Experimentation handbooks of the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s presented science as desirable because it was linked to the “real” (adult) world. Science, the books that came with chemistry sets argued, would help the child (always a boy) master the workings of the materials around him, provide intellectual excitement, or serve as the foundation for future money-making ventures. Even Chemical Magic manuals, which outlined ways to impress friends and family with chemical illusions, emphasized that learning how to give a show would provide a child with managerial skill and the ability to control a crowd.

The “Green Slime” experiment that appears in many of these books is emblematic of the “gross science” approach to pedagogy. This kind of education aims at connecting children with science by aligning them with science’s supposed anti-authoritarian, anarchic bent. As Alice Bell points out in her work on the British Horrible Science series (“Science with the squishy bits left in!”), the “ooey-gooey” science books tend to mock adults, constructing a world in which children’s experiments reveal grown-ups’ foolishness. Because science is “horrible” to adult eyes, it is desirable.

To make slime, kids mix together glue, Borax, water, and food coloring. In the Horrible Science book Really Rotten Experiments, the slime is “evil-looking,” and the narrator recommends adding “two teaspoonfuls of coloring to give it a nice alien-green look.” The child who makes the slime feeds it to his chemistry teacher, Mr. Bunsen. One of the book’s many cartoon illustrations captures his spit-take.

Slime in popular science books, however, is slime approved by the adult world, no matter how carefully the authors of these books try to infuse the practice of slime making with rebellion. Search for “green slime” on Pinterest and you’ll find whole colonies of sanctioned glue-and-Borax slime, pinned as recipes by moms trying to infuse their kids’ lives with the right kind of learning experiences. The gospel of “messy” or “sensory” play holds that preschool children, given the chance to interact with the world through smelling, touching, tasting, and hearing, will develop problem-solving skills, linguistic ability, cooperation, and creativity.

While there’s little implication that adults would try to teach young kids about the characteristics of non-Newtonian substances using this slime, there’s plenty of discussion on the way that sensory play allows children to “act like scientists,” gathering data through their fingertips. Parentally supervised green slime, made at the kitchen table in a large mixing bowl, is one of many ways that the crafty mom enriches her kid’s life. Well-intentioned parents and science teachers are following Nickelodeon’s lead, capitalizing on the inherently kettish qualities of slime in an effort to sell them science.

Green slime, in all of its gloppy, gross glory, shows how rebellion has been co-opted at the molecular level. Kids’ commercial culture has taken the principles of ket to the bank. It can’t be a coincidence that, during the same decades that saw the ascendancy of green slime, kids have enjoyed fewer and fewer opportunities to go outdoors and play by themselves. Chances to mess around in the world without adult supervision have dwindled. Green slime—As Seen on TV or mixed up by Mom—takes the place of mud pies, pond algae, and the guts of that bird that’s been moldering by the neighbor’s fence for a few weeks. If green slime had a tagline, it’d be Gross™, for Indoor Kids.

| An ongoing series about the hidden lives of ordinary things |

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/02/ode-to-green-slime/385088/