"This is not a replacement for people or human contact," said the designer Albert Lee of his new creation, an app called Emojiary. I wanted to believe him.

Every day you get a text from the Emojiary bot. It asks how you're doing. You write it back, texting out your most visceral feelings, and it accepts them without judgment. At least, none that I was able to sense.

This is all meant to be a daily moment of cathartic introspection; completely candid self expression. The name is a portmanteau of emoji and diary. The concept is a portmanteau of loneliness and connection, or emotional illiteracy and anarchy. The bot encourages you to communicate in emojis, but you can also add words. Everything you say is logged on your iPhone, and the idea is that if you're diligent and reply every time it asks you what's up, eventually you have yourself a journal. You can look back at your responses, remembering the good things and feeling nostalgic, or remembering the bad and feeling resilient.

By prompting you every day with a text, and asking only for emojis, as opposed to the mental strain of finding words, it's meant to be easy. And, rather than foreshadowing the decline and fall of emotive linguistics, talking with Emojiary is supposed to be an adjunct to traditional expressions of emotion. It's, in Lee's words, "an activity to support you in increasing self-awareness."

Self awareness is, increasingly, in short supply. Even as recent research suggests that there may be only four categories of human emotion, instead of the previous model that posited six, people are generally poor at recognizing them in themselves. Most of us take little if any time to consciously break them down. Reflective writing, particularly in a journal, has been shown to have health benefits both physical and emotional, increasing control and creativity, decreasing anxiety, depression, and rage. But it's hard to do. Emojiary, or at least its interactive approach, may be a solution.

"Journaling has a lot of known benefits," Lee said, "but it's a super, super high friction problem because you put a blank page in front of someone and they're like, 'I don't know what to do.'"

Lee is founder of a tech company called All Tomorrows whose mission is to "support emotional well-being" and in the process undergird "a kinder, more self-aware society." Tough to argue with. The company rolled out Emojiary in late November, to understated positive reviews. Some people, like me, did not know how to feel about it. And still do not. Though, it makes sense.

There is a lot of research on the health benefits of introspective writing of the sort you do when keeping a journal (the term journaling just never felt okay to me). Earlier this year I talked with Qian Lu, director of the culture and health research center at University of Houston, where she looks at psychosocial and cultural influences on health like expressive writing and emotional regulation. She did a study recently where she asked breast cancer patients to do expressive writing and found improvement in several health metrics, including levels of stress and positive affect, and overall quality of life.

Another study of introspective writing showed effectiveness in reducing severity of irritable bowel syndrome.

Lu's work, like Lee's, was inspired by a paradigm they attribute to the work of James Pennebaker, who is now chair of the department of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, on the link between linguistic expression and health outcomes in the 1980s. He asked people to write about feelings related to a stressful event for 20 minutes and found that in just three or four writing sessions, people saw improvements in physical health and took fewer days off of work due to illness.

Later an influential 1999 study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that when people with asthma wrote about a stressful event in their lives, their lung function improved. The amount of air they could force out in a single breath actually increased by 19 percent. Those who wrote about a "neutral topic" did not improve. (As a writer on the Internet, I paused for a long time at the idea of a neutral topic.) Similarly, arthritis patients who did the same rated their symptoms as less severe after reflective writing.

David Spiegel, now a professor of medicine at Stanford, wrote in the same journal at the time, “We have been closet Cartesians in modern medicine, treating the mind as though it were reactive do but otherwise disconnected from disease in the body.”

Lee and Lauren McDevitt, a partner at All Tomorrows, came to the journaling idea through immersive field research. "One of the things that we kept hearing over and over again was this desire for increased self reflection," Lee said. "People would say things like, 'Things are so crazy with me. I think I kind of know what's going on with me, but I don't really know.'"

In talking specifically about developing a journal platform, the solution seemed to be to make things visual and simple. The two objections people had to more traditional journaling platforms were that they didn't know how to put their emotions into words, and they think faster than they type.

"One thing we found is that feelings can be kind of abstract," McDevitt told me. "When you first start to think about how you're feeling, you might not know how to describe that exactly in words. So the emojis are this first toe in the pool to sort of get a read on how you're feeling."

"When people were faced with the visual emoji," McDevitt said, the cognitive load was decreased to the point where people were like, I think I can actually access this.'"

"At first blush, it may seem kind of silly or goofy, but we realized that the existing emotional lexicon that exists within the emoji set right now is actually really, really useful," said Lee. The app features some original, never-before-emoted illustrations, in addition to the standard emojis we all know and love and hate and ... feel other ways about.

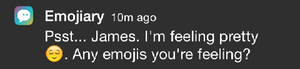

I tried it out, and it went like this.

Just to be clear, I'm the one with the white text box.

And it did!

Click

Show a friend?

The joys of human connection.

The obvious objection to all of this is that choosing emojis to express yourself is not, like writing, generative. You are checking a box. The process doesn't preclude meaningful introspection, but it doesn't require it.

When Lu asked cancer survivors to write about their personal stories, she told me that she was really surprised at the thought processes that emerged. She believes it was the result of diving deep into one's own head. When her breast cancer patients wrote for a half hour, the things they seemed to be feeling were actually, in Lu's words, "very different from if you gave them a standardized questionnaire or just asked them how they feel."

I never got deep at all, but after even just a few days, it was hard to feel like I wasn't slipping into a weird relationship with the program, the text equivalent of the Scarlett Johansson-voiced algorithm in Her. Why are you so interested in me, bot? I know, it's because you're a bot that's doing its bot job. Or because you love me, and only me, forever.

Over time, Lee told me, several beta users of the program came to want more from the bot. "They appreciate the chat, and they'd love a little bit more interaction," said Lee. "We try to manage expectations. We're like, this bot, it's really not the smartest bot."

Don't listen to him, bot.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/12/ew-feelings/383475/