Clik here to view.

Randall Munroe, the creator of the webcomic XKCD, does amazing work. His storytelling ability, and the love he clearly has for his subject matter, make XKCD like little else on the Internet.

But this latest comic of his? I’m not so sure about it.

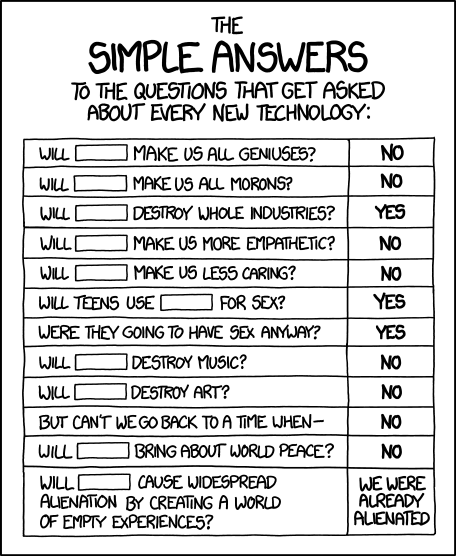

Here it is:

Clik here to view.

What’s going on here? First, and at its simplest, this is a straightforward critique of the most sensational claims made about new technologies (especially new information technologies). You know the type.

Which, yes, OK. Good on Munroe for replying to Jonathan Franzen (“Will ____ make us less caring?”) and those like him, fretting about how the precious media diets they grew up with are perishing. And good on Munroe, too, for mocking the wide-eyed enthusiasm of Silicon Valley boosters (“Will ______ make us all geniuses?”), or at least those who forever praise the products that pad their pockets.

But, I don’t know. This comic reminds me of an earlier drawing by Munroe, a piece that Baylor professor and sometimes-Atlantic contributor Alan Jacobs wrote about at the time. In that comic, Munroe listed a litany of concerns about technology, printed in the press between 1871 to 1915. Year after year, quote after quote ticks by, and each passage essentially laments the same refrain: “In olden times it was different.” By the end of the comic, fretting over—or even discussing—technological change at all seems ridiculous.

Or at least, the comic wants it to seem ridiculous. I agree with technology critic Michael Sacasas, who wrote earlier today:

Both [of these comics] exhibit a certain cavalier “nothing-to-see-here-let’s-move-it-along” attitude with regards to technological change. In fact, one might be tempted to conclude that according to the xkcd philosophy of technology, technology changes nothing at all. Or, worse yet, that with technology it is always que sera, sera and we do well to stop worrying and enjoy the ride wherever it may lead.

Que sera, sera: Whatever will be, will be. Hands off! No need to talk about any technologies at all, or anything they bring about. Just let them wash over you.

Now, Munroe’s questions may be “simple,” and “simple” may be as far as he intends their commentary to be. But inspect some of them individually and they don’t exactly stand up to the scrutiny.

“Will _____ destroy art?,” for example. Munroe supplies the brief answer: “No.” And indeed, sure, no new technology has ever “destroyed art.”

But within two generations of living memory a technology debuted that greatly diminished the role of oil-painted portraiture. We still feel the tentacles of that change: My phone doesn’t have mini-oil paints, and no one’s sending self-porties to each other. We have cameras and photography now.

And within one generation of living memory, the nature of entertainment was changed by technology. Live theater used to the cheapest, most widely available way to watch actors; now, it’s just one more option among television and movies.

And, like, seriously, movies! Film is crazy. Can we not say that, to a 19th century novelist, talking pictures would seem to so alter the definition of art that it might be tantamount to its destruction?

Ditto “Will _______ make us more empathetic?” “No,” says Munroe. I agree to a degree. No technology will make everyone treat everyone else more excellently.

But it seems to me that empathy doesn’t only constitute the warmth and charitable understanding which we extend to the human beings in our lives. If I better understand the life, decisions, and internal worldview of someone in the past, for example, don’t I have empathy (of a sort) for them? And if technology made that possible, then didn’t it make me more empathetic?

The same problem mars Munroe’s last question, “Will _____ cause widespread alienation by creating a world of empty experiences?” This is the question that provoked Sacacas to write a reply, and he explains his frustration with the question better than I can:

Alienation may be a fact of life (or maybe that is simply the story that [modern people] tell themselves to bear it), but it has been so to greater and lesser extents and for a host of different reasons. Pointing out that we have always been alienated is, consequently, the least interesting and the least helpful thing one could say about the matter.

Back when the first of these two comics came out, Jacobs sighed at its larger message: “Even if people were wrong to fear certain technologies in the past, that says absolutely nothing about whether people who fear certain other technologies today are right or wrong. It’s an irrelevant datum.”

Exactly. Munroe means well by highlighting the uselessness of certain questions about technology. But, in doing so, he seems (almost accidentally!) to foreclose all the knotty complexity—and all the terrifying historical change—which those “simple” questions can reveal.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.